The Mountains, the Sun, and the River

Why do millions of Indian and Tibetan children in India draw the same pastoral scene—mountains, an S-shaped river, a hut with trees and line drawing birds? A reflection on how education systems teach reproduction over observation, and what this reveals about the invisible templates shaping our thoughts, beliefs, and sense of self.

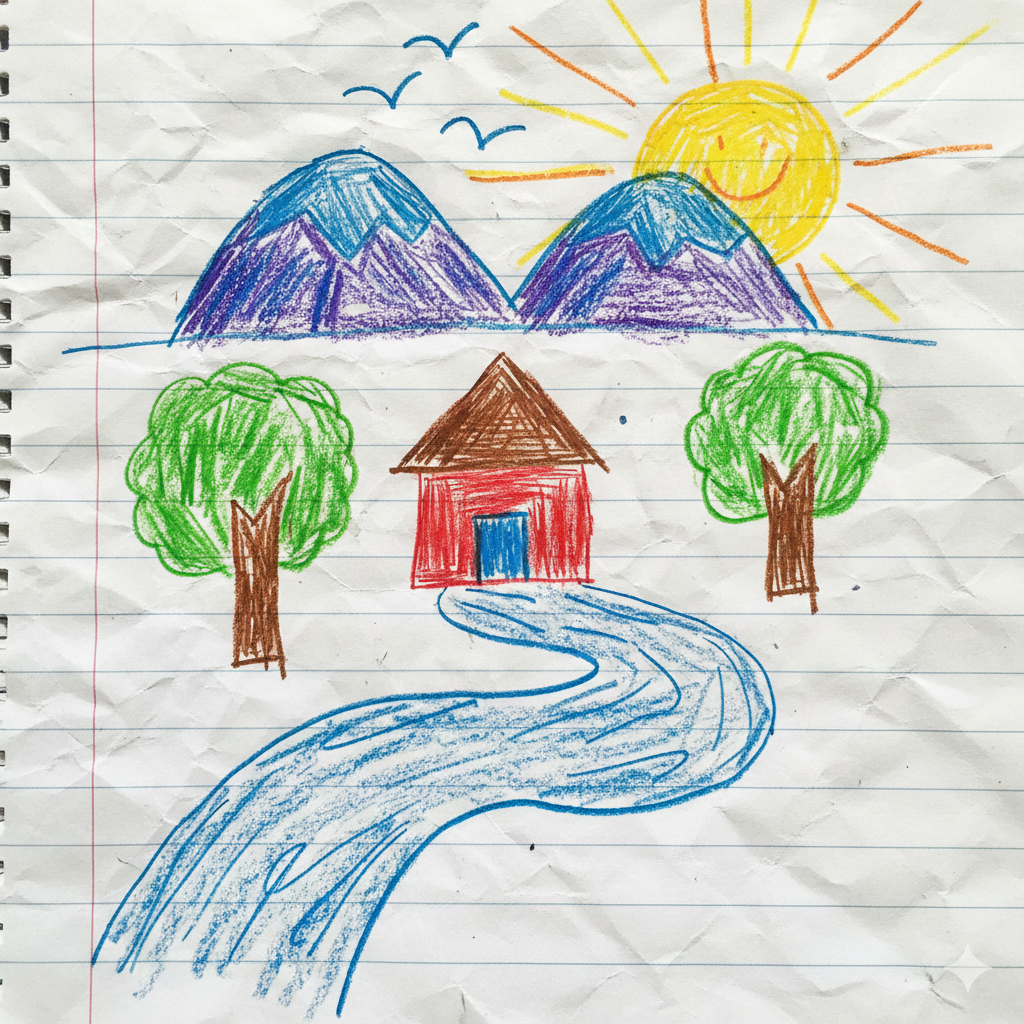

A child's drawing of mountains, sun, river and hut - the universal Indian childhood drawing

The Indian poet Javed Akhtar once made an observation that stopped me mid-thought. He noted that children across India—north and south, city and village—when asked to draw something, produce nearly identical images: mountains in the background, a sun with radiating lines peeking from behind, a small hut, an S-shaped river curving around it, trees standing nearby, and line drawing birds in the sky.

I grew up in India. I drew that picture. I still draw that picture.

The sameness is uncanny. How do millions of children, many of whom have never seen mountains, who live among high-rises and auto-rickshaws and crowded markets, arrive at the same pastoral scene? They could draw their street. Their building. The park where they play cricket. But they don’t.

Because that’s not what they were taught a drawing looks like.

Somewhere along the way, this composition became the template. It appears on blackboards, in notebooks, demonstrated by teachers as this is how you draw a scenery. The S-river is simple. The triangle-on-square house is geometric and achievable. The sun with rays is iconic. It works. It’s reproducible. And so it reproduces—across decades, across regions, across millions of small hands holding pencils.

The children are not failing. They are succeeding. They are doing exactly what was asked: reproduce the correct answer.

But here is what quietly happens in that moment of reproduction.

A child in Chennai who has only known the sea learns that her actual world is not the subject. A boy in a Delhi apartment learns that observation is irrelevant to the task. What matters is matching the template. The teacher’s version is the truth. Deviation isn’t exploration—it’s error.

What quietly weakens is the link between I see, I interpret, and I trust my interpretation enough to put it on paper. That chain gets replaced with a simpler one: authority provides, I reproduce.

This is not a failing of children. It’s not even, in any simple way, a failing of teachers who are themselves navigating overcrowded classrooms and standardized expectations. It’s a system optimized for something specific—and that something is not the cultivation of individual perception.

I sometimes wonder what it would look like if a child were taken outside first—not to be shown what to draw, but simply to look. To notice how light falls on a particular wall at a particular hour. To observe that the tree outside the window has a shape unlike any template.

What if the drawing that emerged was rougher, stranger, more wrong by any standardized measure—but carried something else? The child’s own seeing. Their own small act of saying this is how the world appears to me.

I don’t know if this would be better. I don’t know what we might lose in the trade. But I find myself curious about what such a person might carry into adulthood—someone trained early to observe, to interpret, to trust their interpretation enough to act on it.

I’m not here to condemn a system that has produced brilliant engineers, doctors, and scholars. The template works for many things. Mastery often begins with imitation.

But I find myself wondering about what we might be trading away. When a child learns that the correct river is S-shaped regardless of any river they’ve actually seen, what else do they learn to override? Their curiosity? Their doubt? Their sense that something doesn’t quite match what they’ve been told?

I don’t have a tidy conclusion. I’m not sure I want one.

But I notice that the question extends beyond drawing. If this is how I learned to represent a landscape, where else might the same mechanism be at work?

How I think a career should progress. What I believe a good relationship looks like. How I define success, happiness, a meaningful life. My opinions—are they seen, or received? Even how I think, how I argue, how I structure a thought.

The drawing is innocent. But it reveals a mechanism. And once you see the mechanism in one place, you have to wonder how far it extends. The deeper implication is unsettling: I may not be the author of much of what I assume is “me.”

I’ll leave you with this: the next time you have occasion to draw something—anything—notice what your hand reaches for. Is it the world in front of you? Or is it the template you learned long ago, the one that told you what a drawing is supposed to look like?

And if it’s the template, you might ask yourself, gently, without judgment:

What else am I reproducing without seeing?

Disclaimer: The insights and narratives shared here are purely personal contemplations and imaginings. They do not reflect the strategies, opinions, or beliefs of any entities I am associated with professionally. These musings are crafted from my individual perspective and experience.