The Study Companion I Wish I'd Had

On studying Buddhist texts alone, the questions that pile up, and a tool that finally feels like what we've been missing.

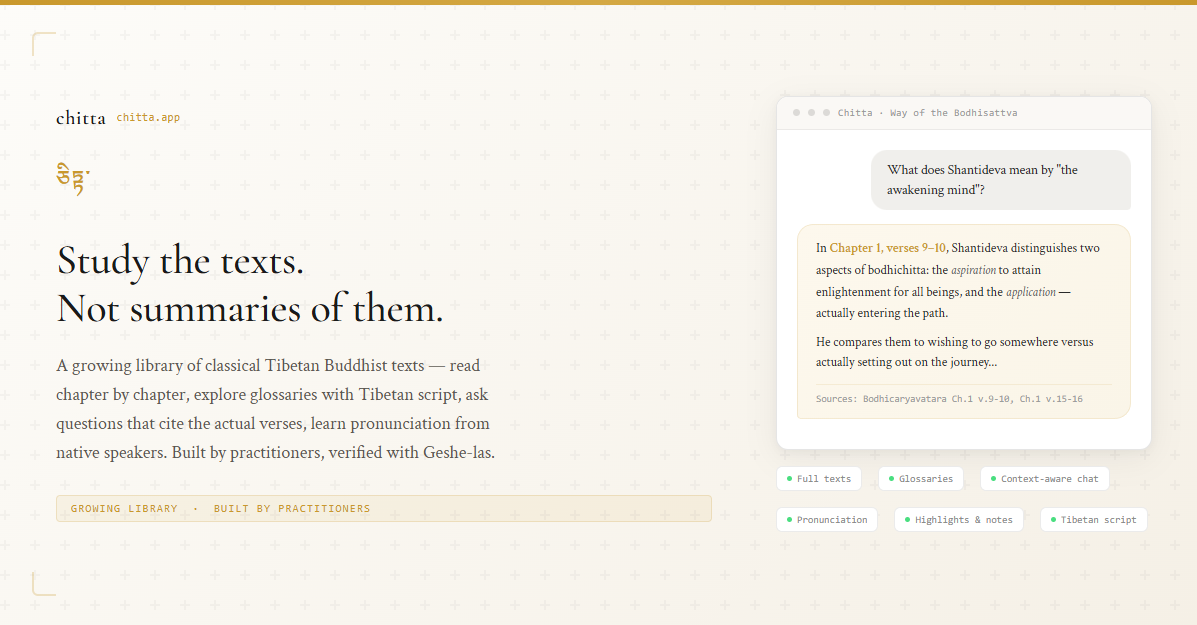

Chitta Study Companion

I want to tell you about a problem I’ve had for years, and why I think it finally has a solution.

The Problem with Studying Alone

I’ve written before about conversations with Geshe-las in New York — about truth, about emptiness, about the nature of reality. Those conversations changed how I think. But here’s the thing about conversations with Geshe-las: they end. The Geshe-la goes back to the monastery, or you go back to work, or life simply carries on, and you’re left with your notes and your half-understood insights and a pile of questions that arrived too late.

I have always been drawn to studying Buddhist texts. Not casually — I mean sitting with the Bodhicaryavatara or Words of My Perfect Teacher and trying to actually understand what’s being said. Verse by verse. Concept by concept.

And every time, the same thing happens. I read a passage and something catches fire. Then three paragraphs later, a term appears that I don’t fully understand — bodhichitta, pratityasamutpada, the two accumulations — and I stop. I open another tab. I search. I find seventeen different explanations ranging from academic papers to Reddit threads. Half of them contradict each other. I lose the thread of the original text. The fire goes out.

Or worse: I think I understand, but I’m wrong, and I carry that misunderstanding forward into everything I read after it.

This has been my experience for years. Not because the texts are inaccessible — they’re beautiful, and many translations are genuinely good — but because studying a text in isolation, without someone to ask, is like navigating a city without a map. You can do it. You will eventually get somewhere. But you’ll spend a lot of time lost.

What I Wished Existed

I used to think about this a lot. Christians have extraordinary study tools — apps that let you cross-reference verses, read commentary from multiple traditions, look up original Greek and Hebrew, all within the same interface. The Quran has similar platforms with Arabic text, recitation, and tafsir side by side. Jewish scholars have had this kind of infrastructure for centuries.

Buddhist practitioners? We have PDFs. Maybe a few scattered websites with partial translations. If you want a glossary that includes the Tibetan script alongside the English, good luck. If you want to ask a question about a specific passage and get an answer grounded in the actual text — not someone’s blog post or a generic overview — there was simply nothing.

I’m not talking about meditation apps. There are plenty of those, and some are quite good for what they do. I’m talking about study. The patient, detailed work of sitting with a text and understanding it. The kind of study that monasteries have supported for a thousand years, but that laypeople — especially those of us in the diaspora — have almost no infrastructure for.

I wanted something simple: a place where I could read a text chapter by chapter, look up terms without leaving the page, and ask a question when I got stuck — and get an answer that pointed back to the verses, not to the internet.

What Should Exist

So I started thinking about what the right tool would actually look like. Not a meditation app. Not another website with scattered translations. Something built around the study itself.

It would let you choose a text — the Bodhicaryavatara, the 37 Practices of a Bodhisattva, Words of My Perfect Teacher, the Jewel Ornament of Liberation — and study it chapter by chapter. It would have a glossary that includes Tibetan script, not as decoration but because the original language matters. And it would have a study companion you could ask questions to — one that searches the actual text you’re reading, not the internet.

Ask about patience while reading Shantideva’s sixth chapter, and it should respond with references to Shantideva’s verses. It should stay within the text. It shouldn’t wander off into some other tradition or some wellness blog’s interpretation of what Shantideva might have meant.

You should be able to go to the passage in Words of My Perfect Teacher about the blind turtle — Patrul Rinpoche’s famous analogy for the rarity of precious human birth — and ask a question, and get a response that cites the specific chapter, connects it to the broader context of the preliminaries, and uses vocabulary consistent with the text you’re reading.

It should feel like studying with someone who has actually read the book.

That’s Chitta. That’s what it does.

Why This Matters

I want to be clear about what Chitta is and what it isn’t. It’s a study companion. It is not a teacher. It cannot replace a Geshe-la’s guidance, and it doesn’t try to.

But as a companion for the hours between teachings — the late nights when you’re sitting with a difficult passage, the early mornings when a question surfaces that you won’t be able to ask anyone until next week — it fills a gap that I didn’t realize was so wide until something finally filled it.

And the Tibetan script. I cannot overstate how much this matters. I’ve written at length about what we lose when we lose our language. Seeing བྱང་ཆུབ་ཀྱི་སེམས alongside “bodhichitta” isn’t decoration. It’s a bridge. It keeps the original language present, visible, connected. For those of us who can read Tibetan, it deepens the study. For those who can’t yet, it plants a seed — a reminder that these teachings have a home language, and that language is worth learning.

The Timing

I’m writing this now because of what just happened in America. Nineteen monks walked 2,300 miles from Fort Worth to Washington, D.C. Nearly six million people followed them. The Walk for Peace opened something in this country — a curiosity about Buddhism that I haven’t seen in my lifetime.

People are searching right now. They want to know what Buddhism is, what the teachings actually say, where to begin. And for once, there’s somewhere to send them that isn’t a Wikipedia article or a meditation app. There’s a place where they can sit with the actual texts — the same texts studied in Sera, Drepung, and Ganden — and begin.

The Tibetan script, the text-grounded responses, the honest disclaimer about seeking a teacher — these are the details that matter. They’re the difference between something built for a community and something built from within it.

What I’d Say to Someone Starting Out

If you’re new to Buddhism — if the monks walking across America stirred something in you and you’re not sure what to do with that feeling — here is what I’d suggest.

Pick up a text. Not a summary, not an overview, not someone’s interpretation. A text. The 37 Practices of a Bodhisattva is short and luminous. The Way of the Bodhisattva will rearrange something inside you. Words of My Perfect Teacher will meet you exactly where you are.

Read slowly. When you don’t understand something, sit with it. Ask questions. If you have access to a teacher, ask them. If you don’t — and many of us don’t, not regularly — use the tools that are finally beginning to exist.

And when you’re ready, find a teacher. A real one. In a lineage. Because the texts will take you far, but there are places only a living teacher can lead you. The tradition has always known this, and no technology changes it.

But between now and then — between the curiosity and the teacher, between the question and the answer — it helps to have somewhere to study. It helps to not be alone with the text.

That’s what I wished we had. And now, it seems, we do.

Disclaimer: The insights and narratives shared here are purely personal contemplations and imaginings. They do not reflect the strategies, opinions, or beliefs of any entities I am associated with professionally. These musings are crafted from my individual perspective and experience.