Roots and Reconnection: A Tibetan Family's Summer Journey Through Our Communities in Exile

A Tibetan family's journey home to exile—taking our Western-raised children across states to experience their roots through language schools, cultural institutions, and family connections.

Dharamsala, India

Last summer, we packed up our lives for two months and headed to India. The typical tourist route wasn’t what we were after—we wanted something deeper. Our destination was Dharamsala, the seat of the Tibetan Government in exile and home to His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

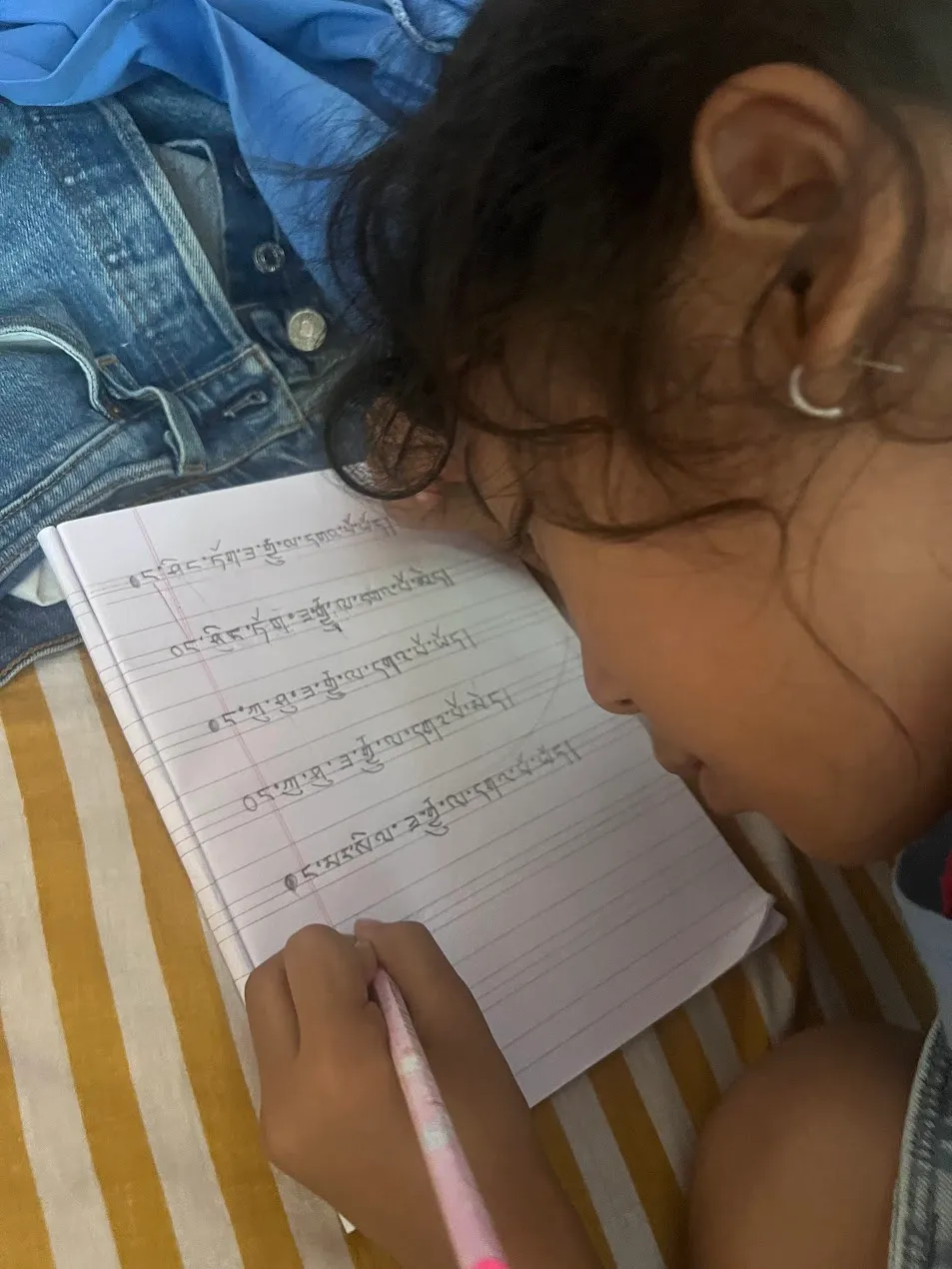

The plan was straightforward: enroll our kids at Petoen School, the renowned Tibetan refugee school famous for its Tibetan language classes. We wanted more than language lessons, though. We wanted our children to experience what it means to be Tibetan in exile, to breathe that air, to walk those streets.

Living in the Heart of Exile

We chose to stay in Gangchen Kyishong—Gangkyi, as locals call it—the administrative center of the Tibetan government in exile. This choice was about immersion rather than just convenience, though the walking distance to Petoen School certainly helped during monsoon season.

In Gangkyi, tourists are rare. Instead, you’re surrounded by the machinery of a government that exists without a country. Office buildings with distinctly Tibetan architecture house departments working to preserve a culture under siege. Government workers in traditional chupa walk the same paths as monks from nearby Nechung Monastery. The famous Tibetan Library sits quietly, holding centuries of wisdom in its halls.

For our kids, this became their daily landscape—the living, breathing reality of Tibetan life in exile rather than postcards or guidebook photos.

Cultural Immersion Beyond the Classroom

While Petoen School provided the foundation, our older daughter Pema’s education extended far beyond regular classes. After school, she took private dramnyen lessons, first with Gen Choenden la, then at the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts, and finally a brief but memorable session with the renowned Jhola Techung la. Watching her fingers learn to coax melodies from this traditional instrument felt like witnessing cultural transmission in real time.

Whenever we had free moments, we explored the various institutions that make Dharamsala a center of Tibetan learning. We spent hours at the Tibetan Library, wandered through exhibitions, and absorbed the displays at the Tibetan Medical and Astro Institutes’ museum. Several monasteries became regular destinations, each offering different glimpses into monastic life and practice.

The Nechung Monastery developed into a daily ritual for the kids. They would peek through doorways and around corners, hoping to catch a glimpse of Nechung and Paldhen Lhamu behind the colorful khatas. These were the natural curiosity of children exploring a world that was becoming familiar rather than formal visits or guided tours.

The Nechung Monastery developed into a daily ritual for the kids. They would peek through doorways and around corners, hoping to catch a glimpse of Nechung and Paldhen Lhamu behind the colorful khatas. These were the natural curiosity of children exploring a world that was becoming familiar rather than formal visits or guided tours.

The Mountains and the People

While the children attended school, my wife and I explored the surrounding hills. We hiked to Bhagsunath, wandered through McLeod Ganj, and pushed ourselves up mountain paths until our legs screamed. The exercise was brutal and exactly what we needed.

Dharamsala, especially McLeod Ganj, has transformed dramatically over the years. What used to be a quiet hippie destination with some Israeli gap-year youths and students of Tibetan Buddhism has become a bustling tourist hub. Roads are packed with cars, shops and restaurants overflow with customers from all over the world, and Indian tourists now make up a significant portion of the visitors.

The most telling insight came from conversations with taxi drivers and local Indian business owners. They all acknowledged the same reality: their business revolves entirely around His Holiness the Dalai Lama. When he’s in town, commerce booms. When he travels, everything slows down. This reminded me of similar stories from Bodhgaya, where local Indians invest lakhs of rupees setting up shops before His Holiness is scheduled to arrive. There’s an extraordinary ripple effect of positivity wherever he goes—economic, spiritual, cultural.

The real discovery, though, was in the people we met. Working with Himalayan Nepali populations back in New York had taught me something about the interconnected nature of these mountain communities. So when I reached out to Ravinder Rana, president of the Gurkha Association Dharamsala, it felt like completing a circle.

Rana ji invited me to his home, introduced his family, and we talked about collaboration between Gurkhas and Tibetans in Dharamsala. He shared stories of playing soccer with Tibetan friends in the old days. Simple memories, but they pointed to something larger—how communities find ways to support each other when they’re far from home.

Evening Connections

Most evenings belonged to friends and family. I spent nearly every day with my cousin brother Tsultrim, conversations that now carry extra weight since he passed away after we left Dharamsala. Those daily talks, the easy familiarity of family—you don’t realize how precious they are until they’re gone.

I also reconnected with Buchung D Sonam, learning about his work with Tibetwrites, and met Sherab Woeser, who told me about Tibet Fund’s operations in India. Along with my friend Shelly Bhoil, I had long discussions with both the Director and Artistic Director of the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts about various projects they were developing.

These were the natural conversations that happen when you’re living somewhere rather than just visiting.

Beyond Dharamsala

After our time in Dharamsala, we traveled to Kalimpong to meet with folks from Gangjong Doeghar, one of the oldest cultural institutes in Tibetan exile. The founder, A Doega la, had passed away a few years earlier, and his son Samdup had taken over the responsibility of preserving the institution.

We booked us at the Gompus Hotel—the place where I celebrated some of my most cherished childhood birthdays. My parents would drive from Gangtok to visit me at Central School for Tibetans, and staying at Gompus felt like the grandest thing in the world. I was excited to share those stories with my kids, to show them this special place from my past.

Memory, it turns out, can play cruel tricks. What had seemed like a magnificent hotel in my childhood eyes now looked small and cramped, wedged into a congested area with electrical wires running everywhere. The moment we walked through the entrance, cigarette smoke hit us like a wall. Our room was worse—moldy walls, a bathroom with a green, slippery floor, and an actual hole in the wall so large it looked like someone had started demolishing the place with a hammer and then just… stopped.

So much for nostalgic storytelling. We quickly moved to the Mayfair (previously known as Himalayan Hotel), and I quietly shelved my childhood birthday tales for another time. Sometimes it’s better to let beautiful memories stay in the past where they belong.

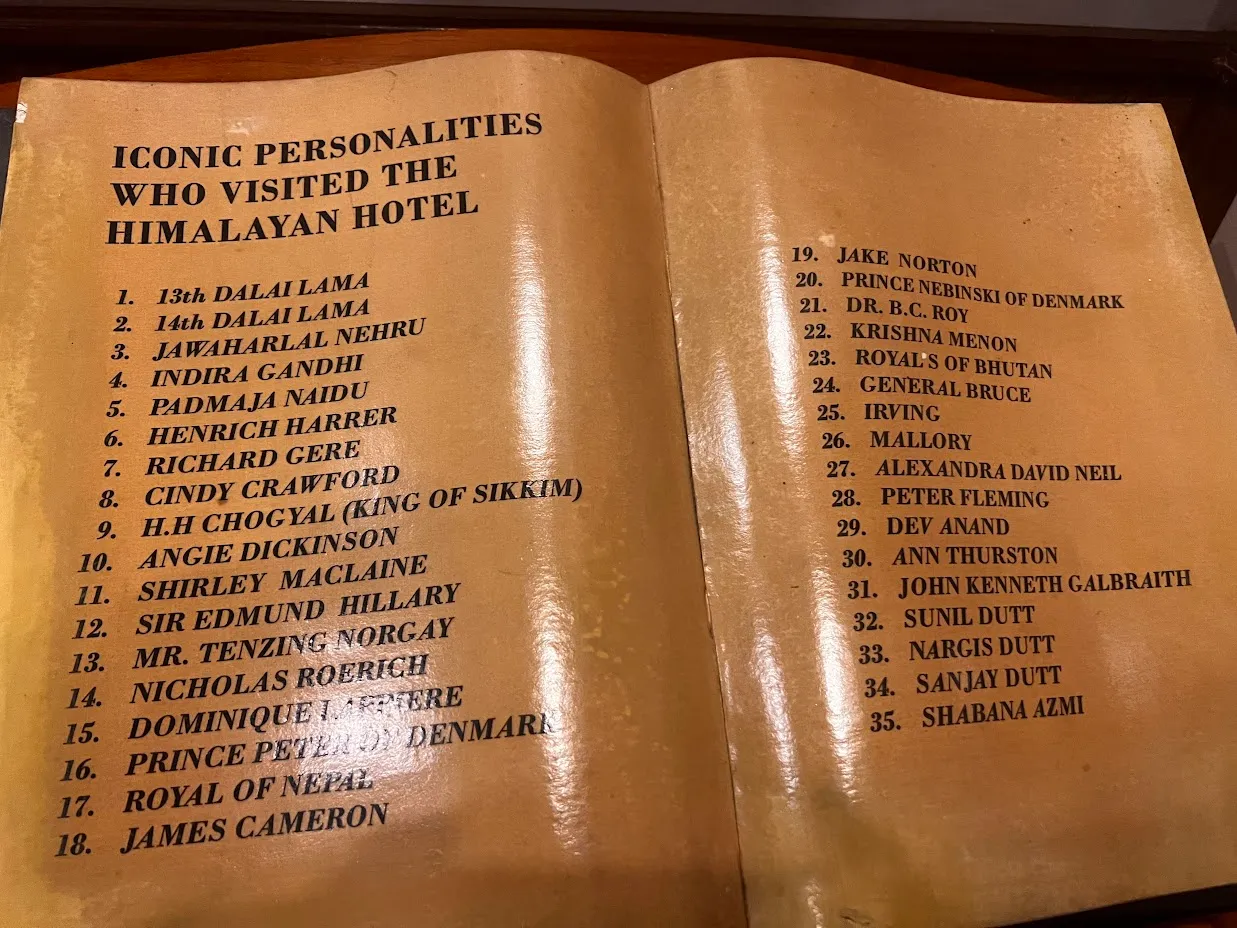

Image: The Mayfair, Kalimpong.

Image: The Mayfair, Kalimpong.

Ironically, our backup choice turned out to have far more historical significance than my childhood hotel. The Mayfair was built in 1905 by Scottish diplomat David Macdonald as a family residence. Macdonald served as British Trade Agent in Tibet and Sikkim and played a crucial role in aiding the 13th Dalai Lama’s escape from Tibet into India around 1910. His pivotal role earned him special recognition from the British colonial government, who offered him a choice between a formal title or a prime parcel of land in Kalimpong. Macdonald chose the land adjacent to his family home, and on that plot, he and his son-in-law built the Himalayan Hotel—now the Mayfair Himalayan Spa Resort where we stayed.

The hotel stands as a witness to a pivotal era of Tibetan exile, British-Indian diplomacy, and Himalayan exploration, having supported and been frequented by leading figures during the Dalai Lama’s escape and stay in Kalimpong, along with subsequent visits by dignitaries and celebrities over the decades.

The hotel stands as a witness to a pivotal era of Tibetan exile, British-Indian diplomacy, and Himalayan exploration, having supported and been frequented by leading figures during the Dalai Lama’s escape and stay in Kalimpong, along with subsequent visits by dignitaries and celebrities over the decades.

Sitting with Samdup, we talked through the challenges facing cultural preservation in exile—funding constraints, changing priorities among younger generations, the constant balance between tradition and adaptation. We also discussed opportunities, ways to connect with diaspora communities, potential collaborations.

Sitting with Samdup, we talked through the challenges facing cultural preservation in exile—funding constraints, changing priorities among younger generations, the constant balance between tradition and adaptation. We also discussed opportunities, ways to connect with diaspora communities, potential collaborations.

What struck me most was the particular challenge Gangjong Doeghar faces in Kalimpong. Just like Tibetans in the West struggle to teach Tibetan to their children when surrounded by English, Tibetans in northeast India—especially in Kalimpong—face a similar situation where everyone speaks Nepali. My deep admiration goes to how Gangjong Doeghar has stood the test of time despite these linguistic pressures. It’s much easier for Tibetans in Dharamsala or other Tibetan settlements around India to maintain their language and culture when they’re surrounded by Tibetan-speaking communities. In Kalimpong, maintaining Tibetan identity requires swimming against a much stronger current.

This visit went beyond conversation. I was able to help materialize several projects for Gangjong Doeghar and connect them with donors who understood the importance of their work. It turned out to be my most productive project during our entire time in India.

Coming Home to Sikkim

From Kalimpong, we headed to Sikkim, to my parents’ house, where the pace finally slowed down. After weeks of intense cultural immersion and project discussions, we settled into leisurely family time.

Even in relaxation, though, connections kept forming. We learned about a local Nepali fruit seller whose daughter was a recent graduate struggling to find employment. Through our network, my good friend Raju Lama was able to connect her with an NGO that ran schools high up in the mountains. Small interventions like helping the fruit seller’s daughter matter—especially when you see how one conversation can change someone’s trajectory, and when you have friends willing to act on those opportunities. I want to give a special shout out to Raju and appreciate his incredible work.

Raju, besides being the most popular Nepali singer, is a well-respected philanthropist and social worker. We’ve collaborated on several projects over the years, and what I admire most is his readiness to jump into any situation where he can help others. During the devastating 2015 earthquake in Nepal, Raju immediately threw himself into relief work—delivering food across the country, literally rebuilding a bridge that connected two villages, then going on an extended hike with his band to play music village after village to lift people’s spirits. He continues this social work, and just a few years ago decided to climb Mount Everest and play music there to bring attention to global warming.

We also had a fantastic surprise family reunion. Several of our family members living in Sikkim were joined by others who had come from Europe, creating an unexpected and wonderful gathering.

Our time in Sikkim included a grand tour of the famous Temi Tea Garden. Founded in 1969 by Chogyal Palden Thondup Namgyal, the last monarch of Sikkim, the estate was created to provide employment for Tibetan refugees. He invited British planter Teddy Young from Darjeeling to help establish the operation.

Today, the 100% organic tea is in high demand—about 75% is purchased by Lipton through auctions in Kolkata. While the tea garden no longer has any Tibetan employees and runs independently, most Tibetan refugees have fond memories of this place that once provided them livelihood and hope.

We also toured the Central School for Tibetans in Ravangla and were thoroughly impressed by both the dedicated teachers and bright students there.

What Stays With You

Two months sounds like a long time, but it passes quickly when you’re actually living somewhere. The morning walk to school, the afternoon hikes, the evening conversations—they create a rhythm that becomes normal surprisingly fast.

What lingers goes beyond just the language our kids picked up or the mountains we climbed. It’s the understanding that comes from being part of a community, even temporarily. The Tibetan experience isn’t just about preserving culture in museums or books. It’s about creating life and meaning in places far from home, building connections across communities, and finding ways to thrive despite displacement.

That summer taught us something about resilience, about the difference between surviving and actually living. Sometimes you have to leave your comfortable routines to remember what matters most.

We’re heading back to India in a few days for another adventure, and I can’t wait to see what new stories and experiences lie ahead.

Disclaimer: The insights and narratives shared here are purely personal contemplations and imaginings. They do not reflect the strategies, opinions, or beliefs of any entities I am associated with professionally. These musings are crafted from my individual perspective and experience.